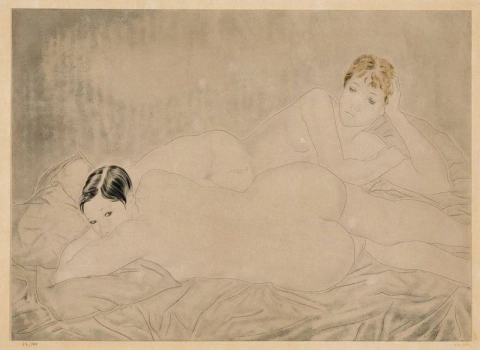

Hand-painted painting reproductions - Movements - School of Paris

Imagine owning a museum-worthy piece of art, created by the greatest artists in history and reproduced by passionate and experienced painters. At POD, we offer you the opportunity to make that dream a reality. We reproduce the works of art of your favorite painters from the School of Paris art movement in the smallest details, so that you can enjoy them in your own home.

Our reproductions are made by experienced artists who use the best materials and techniques. We are committed to providing you with works of art of the highest quality, which will bring joy and inspiration to your family for generations to come.

In the early 20th century, Paris was a city alive with creativity and innovation, a cultural melting pot where artists from around the world gathered to explore new ideas and push the boundaries of art. The city was buzzing with the energy of the avant-garde, and it was within this vibrant environment that the École de Paris, or School of Paris, emerged. This term didn’t refer to a specific institution or a single artistic style but rather encompassed a diverse group of artists who lived and worked in Paris between the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. These artists, hailing from different countries and backgrounds, were united by their desire to break away from traditional artistic conventions and to create something new and revolutionary.

The École de Paris was not defined by a singular style or ideology. Instead, it was characterized by its diversity, its openness to experimentation, and its embrace of different influences. The movement included painters, sculptors, and other visual artists who were often inspired by the innovations of movements like Cubism, Fauvism, Surrealism, and Expressionism, yet they didn’t strictly adhere to any one of these styles. The artists of the École de Paris were pioneers in their own right, each contributing their unique voice to the broader narrative of modern art.

Paris, during this time, was a city of artistic ferment, where the boundaries between cultures and disciplines blurred. The Montparnasse district became a hub for these artists, a place where creativity flourished in the cafés, studios, and galleries that dotted the area. Here, artists like Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine, and Tsuguharu Foujita found inspiration and camaraderie. They were part of a larger international community that included figures like Marc Chagall from Russia, Constantin Brâncuși from Romania, and Diego Rivera from Mexico. Each brought their own cultural heritage to their work, creating a rich tapestry of artistic expression that was uniquely Parisian in its cosmopolitanism.

The early years of the École de Paris were marked by the influence of Cubism, a revolutionary movement spearheaded by Picasso and Georges Braque. Cubism’s fragmented forms and multiple perspectives challenged traditional notions of representation and paved the way for further experimentation. The artists of the École de Paris absorbed these ideas, but rather than imitating Cubism, they each interpreted it in their own way, blending it with their individual styles and influences. This period also saw the rise of Fauvism, with its bold use of color and expressive brushwork, which further fueled the creative energy of the Parisian art scene.

As World War I came to an end, the École de Paris entered a new phase. The 1920s, often referred to as the "Roaring Twenties," were a time of optimism and renewal, and this spirit was reflected in the art of the period. The movement became even more international, attracting artists from across Europe, North America, and Asia. These artists were drawn to Paris not just for its rich artistic heritage but for the freedom it offered—a place where they could experiment with form, color, and subject matter without the constraints of traditional academic art.

One of the defining characteristics of the École de Paris was its embrace of individuality. Unlike other movements that were often defined by a manifesto or a set of principles, the École de Paris was fluid, allowing for a wide range of expression. This diversity is evident in the works of its key figures: Picasso’s exploration of form, Modigliani’s elongated portraits, Soutine’s intense, almost visceral landscapes, and Foujita’s delicate blend of Japanese and Western styles. Despite their differences, these artists shared a common goal—to push the boundaries of what art could be and to reflect the complexities of the modern world.

The École de Paris was also notable for its role in bridging the gap between the traditional and the modern. While many of its artists were at the forefront of avant-garde movements, they also maintained a deep respect for the art of the past. This is evident in the way they drew on a wide range of influences, from classical European painting to non-Western art forms, integrating these elements into their work in innovative ways. This synthesis of the old and the new is one of the defining features of the movement and one of the reasons it remains so influential.

The movement continued to evolve throughout the 1930s and 1940s, even as the world was plunged into the turmoil of World War II. The war had a profound impact on the artists of the École de Paris, many of whom were forced to flee the city or go into hiding. Despite these challenges, the movement persisted, and its legacy continued to grow. After the war, the École de Paris experienced a resurgence as many of its artists returned to the city and new artists arrived, drawn by its reputation as a center of artistic innovation.

The post-war period saw the emergence of a new generation of artists associated with the École de Paris. These artists, while influenced by the earlier generation, brought their own perspectives and experiences to their work. They continued to explore the themes of individuality, diversity, and innovation that had defined the movement from its inception. The École de Paris, now encompassing an even broader range of styles and approaches, remained a vital force in the world of modern art.

Today, the legacy of the École de Paris is evident in the continued influence of its artists and their work. The movement represents a pivotal moment in the history of art, a time when the boundaries between cultures and artistic disciplines were broken down, leading to the creation of some of the most iconic and enduring works of the 20th century. The École de Paris is remembered not just for the individual achievements of its artists but for the way it encapsulated the spirit of an era—an era of experimentation, collaboration, and a relentless pursuit of artistic innovation.

As we look back on the École de Paris, we see a movement that was as much about the city of Paris itself as it was about the artists who lived and worked there. Paris was more than just a backdrop; it was a catalyst for creativity, a place where ideas could flourish and where artists from around the world could come together to create something truly remarkable. The École de Paris is a testament to the power of cultural exchange and the enduring appeal of Paris as a beacon of artistic freedom and expression. It remains a symbol of the city’s unique role in the history of art and a reminder of the transformative power of creativity.